California fights wildfires like wars, but this one may be unwinnable.

This article originally ran on January 9, 2025 in New York magazine.

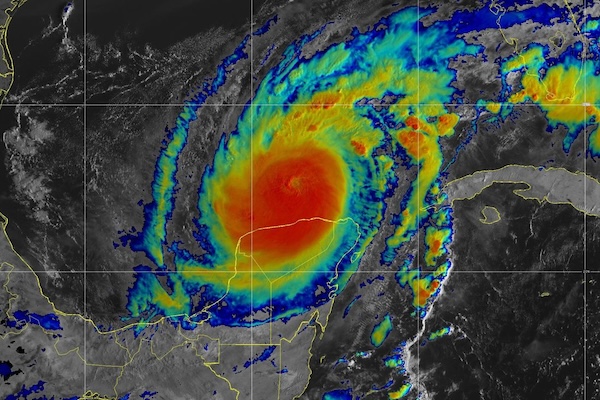

Walls of flames pushed by hurricane-force winds are devouring the Los Angeles basin, leveling whole neighborhoods and overwhelming firefighters. The water streaming from fire hydrants slows to a trickle. Ash rains down over the tens of thousands fleeing their homes, masked against the choking smoke. For Angelenos watching their city burn, there is no prior experience that can help them grasp the scale of what is happening. As a friend texted me from Hollywood, “This may be the biggest wildfire disaster in world history.”

The scale of the destruction is all the more dismaying given how assiduously California has prepared itself to combat wildfires. The state’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, better known as CAL FIRE, spends $4 billion a year on prevention and mitigation. Over the last decade that money has allowed it to assemble an army-like force of unprecedented sophistication and scale, with a staff of 12,000 and an aerial firefighting fleet larger than most countries’ air forces.

Yet in the face of some of the worst fire conditions in over a decade, it hasn’t been enough. Though some 9,000 firefighters were on hand to battle this week’s blazes, they were overwhelmed by the multiple wildfires that moved at hundreds of yards per minute. “We don’t have enough fire personnel in L.A. County between all the departments to handle this,” L.A. County fire chief Anthony Marrone told the L.A. Times on Wednesday.

The problem wasn’t only a shortage of manpower. Even the most formidable human efforts are useless when bone-dry undergrowth is whipped by the strongest winds the area has experienced in years, with gusts up to 100 mph. “When that wind is howling like that, nothing’s going to stop that fire,” says Wayne Coulson, CEO of the aerial firefighting company Coulson Aviation that’s battling the fires. “You just need to get out of the way.”

The winds slackened Wednesday night and on Thursday morning, helping firefighters gain the upper hand against some of the infernos. The city’s fire chief announced on Thursday that the Woodley fire in the San Fernando Valley had been brought under control and that firefighters had made gains against the Sunset fire threatening Hollywood. But other fires still burned out of control and further danger loomed. According to the National Weather Service, humidity remains dangerously low and gusty winds of up to 70 mph are expected between Thursday night and Friday evening. By Thursday morning, five major fires were still burning and tens of thousandsof people were under evacuation orders. Warned the NWS: “Any new wildfires that develop will likely spread rapidly.”

Continue reading How Do You Stop a Hurricane Made of Fire?