To watch Deep Dive MH370 on YouTube, click the image above. To listen to the audio version on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music, click here.

For a concise, easy-to-read overview of the material in this podcast I recommend my 2019 book The Taking of MH370, available on Amazon.

Thanks to our Episode 19 sponsor, Jacob John. His music is available for download here.

If there was one piece of debris, there should have been a lot more. Yet month after month went by without any further discoveries. Then, on February 28, 2016, I received an email from an independent researcher named Blaine Alan Gibson.

Dear Jeff

Please read my post in The Longest Journey [a members-only Facebook discussion group] about the debris my friend and I found in Mozambique. I will be attending the two year commemoration in Kuala Lumpur March 6. I still hope you and I can meet in person soon to discuss MH 370. I am increasingly doubtful about the validity of the Inmarsat data and its interpretation.

Best wishes,

Blaine Gibson

I’d first become aware of Gibson the previous June. Another MH370 researcher who went by the handle Nihonmama had posted a comment on my web page naming Gibson as a retired Seattle lawyer on a self-financed trip around the Indian Ocean region looking for clues about the missing plane. Gibson had just been on a trip to the remote island of Kudahuvadhoo in the Maldives, Nihonmama said, where villagers reportedly had seen a plane in red-and-blue livery fly low overhead the morning after MH370’s disappearance.

This was one of those “fog” stories which serious researchers had always ignored. Eyewitness testimony is notoriously unreliable, and there was no way the Inmarsat data was compatible with the plane’s appearance over Maldives. But Gibson was convinced that the villagers really had seen MH370, perhaps as it headed toward a suicide mission at Diego Garcia. To me, this idea marked him instantly as a crank.

Then in September, Gibson had reported on Facebook that he’d visited Réunion and hunted down Johnny Begue to learn more about the discovery of the flaperon. This was more interesting to me, so I reached out to him and we exchanged a few messages. In one-on-one exchanges he struck me as affable, coherent, and concise, as well as a competent speller, which means a lot when you’re dealing with people on the internet.

Two months later Gibson popped up again. He’d posted on Facebook about a shadowy meeting that supposedly took place in a remote corner of Vietnam two months before MH370 disappeared. In his account, an unidentified arms broker had produced a mysterious Soviet chemical warfare agent, a clear liquid in a glass-lined bottle, and melted a plastic water bottle down to a puddle with a single drop. The locals supposedly had dubbed the stuff “water dissolves metal.” Now Gibson was proposing that MH370’s hijackers had tried to use it to break through the cockpit door but had accidentally caused the hull to depressurize, leading to a hypoxic ghost flight to oblivion.

I mentally re-filed him in the lunatic fringe.

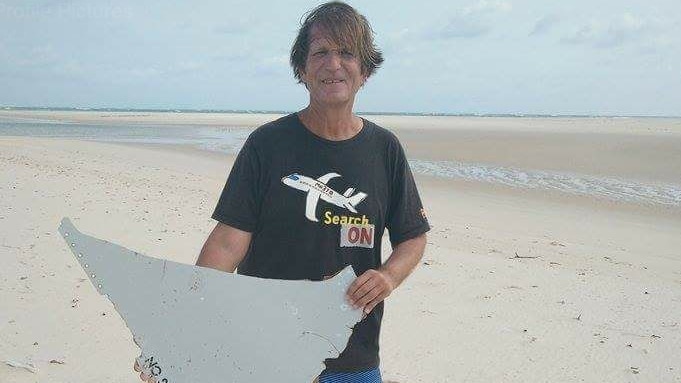

Nevertheless, when I got his February email about debris in Mozambique, I took it seriously enough to click through. I found pictures of a triangular slab of composite with a honeycomb interior, and a note saying that Gibson had found the piece the previous day on a sand bar near the town of Vilankulo. The piece bore the words “No Step.”

Gibson shared his information with some members of the Independent Group, but made everyone swear to secrecy, for reasons that weren’t clear to me. Within a few days the find was made public anyway. Malaysia’s transport minister, Liow Tiong Lai, tweeted that there was a “high possibility debris found in Mozambique belongs to a B777.”

Overnight, a man who’d lurked on the farthest fringes of the story became a worldwide celebrity. Television networks scrambled to interview him. Due our past association, he graciously granted me one of the first interviews, and I talked to him over the phone for 30 minutes for New York magazine. Among the surprising details he revealed was that he’d had the idea to go to Vilankulo after asking Charitha Pattiaratchi, an Australian oceanographer who was working the ATSB, where the highest probability search area would be. Pattiaratchi had recommended the coast of Mozambique.

Gibson had gone out to a sandbar with local boatmen and found “No Step” after only 20 minutes—an incredible stroke of luck.

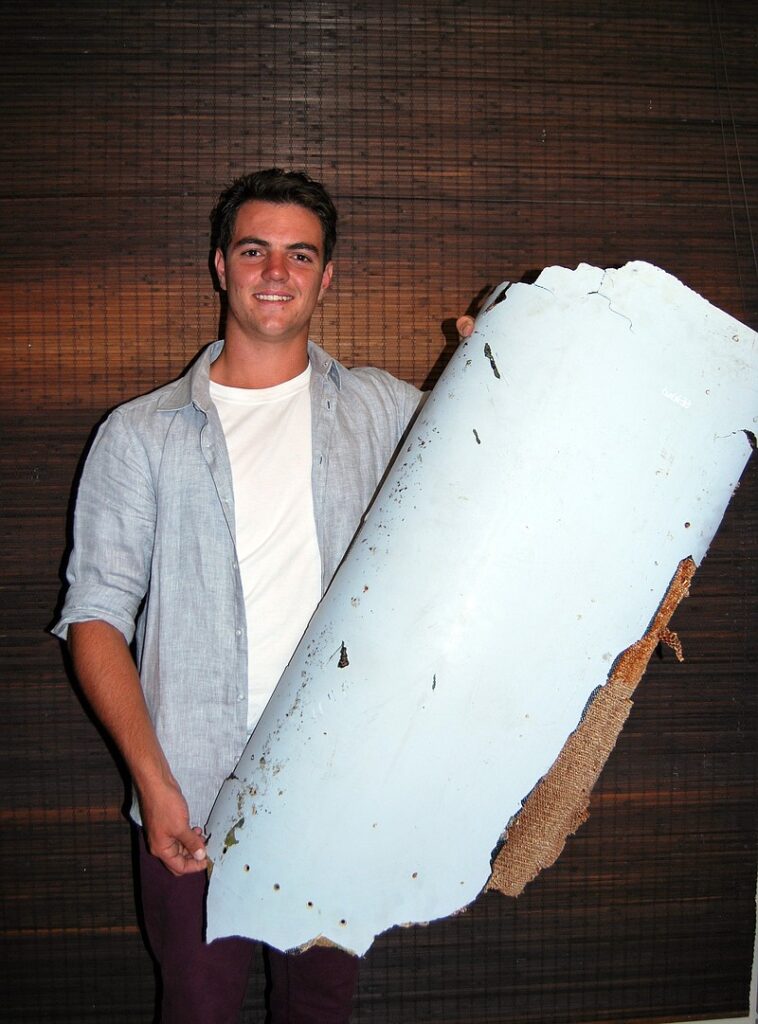

The publicity surrounding Gibson’s find triggered a wave of debris-reporting. On March 11, a South African teenager named Liam Lötter told local reporters that he’d found something similar on a beach near the resort town of Xai Xai in southern Mozambique in December. Only after he’d seen Gibson’s story did he have any idea what it could be. Approximately a meter long, it carried the stencilled code “676EB,” which identified it as a right-hand outboard flap faring from a Boeing 777.

Two weeks later, a man strolling on a beach in Mossel Bay in South Africa found a piece of an engine cowling.

This particular piece had another surprise up its sleeve. After it was discovered, a retired doctor named Schalk Lückhoff piped up and said that he’d noticed that object on a nearby stretch of sand three months earlier, back in December, and had been so struck by it that he took a picture of it. He told a local news station “It was the only object on the empty sands. It was smelly because it was encrusted in rotting mussels so I didn’t handle it, I just took a photograph. It did not occur to me this could be a piece of a plane’s insignia … After the next high [tide] I didn’t see it anymore and assumed it had been taken back into the sea.”

A week after the Mossel Bay piece was turned in a vacationing couple on Rodrigues Island in Mauritius found a chunk of an interior cabin panel. Interestingly this one also had small barnacles on it.

For the first time, the ATSB said that the quantity of debris collected in the western Indian Ocean by itself is useful in reducing the search area: “From the number and size of items found to date from MH370 there was definitely a surface debris field, so the fact that the sea surface search detected no wreckage argues quite strongly that the site where the aircraft entered the water was not between latitudes 32°S4 and 25°S along the 7th arc.”

David Griffin, an oceanographer with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO), led a team that used a computer simulation of how debris might travel over time. They then ran the simulation many thousands of times to show all the different tracks the flaperon might have taken from various points along the 7th arc. Needless to say, this covered a huge swath of the ocean. Nevertheless, it was possible to calculate the zone from which the simulated flaperons would most likely reach Réunion.

As we’ve seen, an important component of this kind of modeling is windage. If an object floats high in the water, the wind will tend to push it along faster than if it were deeply immersed. To come up with a windage value for the flaperon, CSIRO scientists built six replicas of similar shape, size, and weight and set them adrift in the ocean off the coast of Tasmania.

The results were then fed back into the model.

The outcome was puzzling. Most of the simulation runs ended with the flaperon floating far north of Réunion Island. Perhaps, Griffin’s team reasoned, the replicas weren’t accurate enough.

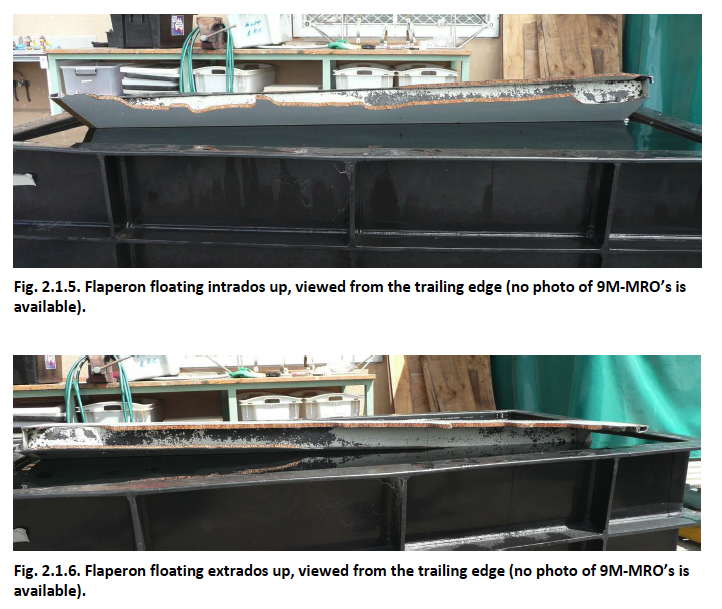

To explore this possibility, the CSIRO team obtained a real Boeing 777 flaperon, then cut it down to mimic the damage experienced by the piece found on Réunion. When they put it in the water, voilà: Compared to the replicas, the real cut-down flaperon floated much more like the original.

However, there’s one striking thing to notice about the real flaperon: its trailing edge sticks way out of the water! Here’s another view:

Here’s a closer look at the portion of the flaperon that floated out of the water all the time. How did a part that sticks so far out of the water get encrustated with animals that live under the waterline?

At any rate, once the new data was fed into the model, it showed that debris starting from within the high-probability search area was more likely to drift to Réunion Island. For the ATSB, this was welcome news. The drift modeling was pointing to the same stretch of ocean as their Inmarsat data analysis.

There were a few problems with this picture, however. One was that, while the CSIRO’s refined model was excellent at predicting that the flaperon would turn up at the right place and time, it didn’t work so well for some of the other debris items. It couldn’t explain, for instance, how a piece of engine cowling had managed to float all the way to the southern tip of South Africa by December, 2015.

As with the flaperon, the CSIRO built a replica of the cowling fragment to test how the piece would have floated. They found that it floated so low in the water that it was virtually unaffected by the wind, and so moved more slowly across the ocean than a high-windage item like the flaperon. When they ran their simulation forward from 35 degrees south, the cowling wound up nowhere near South Africa by the time the real-life object was collected. And some of the modeled low-windage debris washed up on the western coast of Australia where none had in fact been found.

The ATSB’s newly designated search zone had another major problem. It lay within their very first search area, and as such had already been partially scanned. In particular, the area around 35 degrees had been searched out to nearly 20 nautical miles in either direction. If the plane had crossed the 7th arc there and been plummeting near vertically at hundreds of miles per hour, its wreckage should already have been found.

So while the ATSB was making confident public pronouncements, the true situation was much more problematic and baffling. Investigators had developed multiple lines of inquiry into where the plane could have gone, but these lines did not converge. Choose any spot on the 7th arc, and there was a strong reason to believe that the plane hadn’t gone there. South of 39.5S was ruled out because the plane couldn’t fly that far. 36S to 39.5S was ruled out because debris would have floated east to Australia, where none had been found. North of 32S was ruled out because the area had been searched extensively from the air, and no debris had been spotted. That left a pretty narrow hot spot around 35S, but the ATSB couldn’t say how a piece of debris could have floated from there to Mossel Bay, South Africa in a year and a half. (The seabed there had also been searched). It was hard to make a plausible case that MH370 had gone anywhere.