We’re back! Andy and I took a week off to catch our breath, and now we’re back on the case. This week we look at where the plane could have gone if it didn’t go into the remote southern Indian Ocean. According to the Inmarsat data, it would have flown to the northwest, but that raises another question: if it flew over mainland Asia, why wasn’t it picked up by anyone’s military radar?

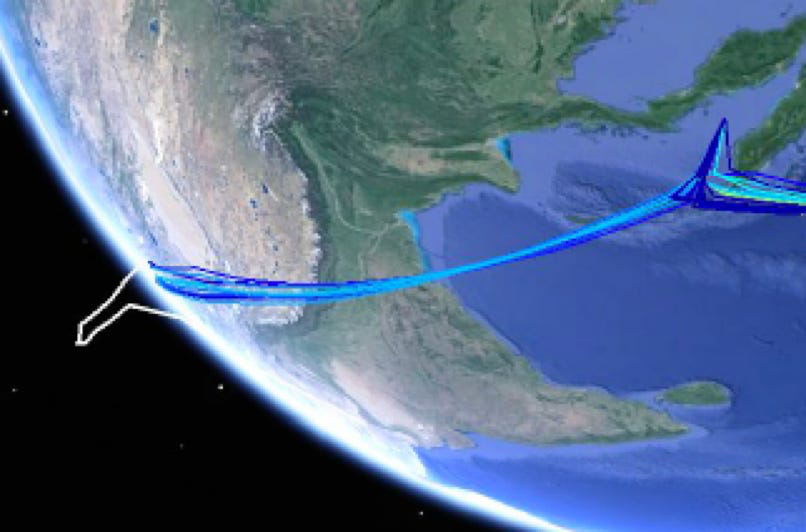

As you’ll recall, when Australian scientists applied the technique of Bayesian inference to the BTO data, they found that it indicated that the plane might have taken one of two flight paths, one to the north, one to the south:

Zooming in on the northern route and rotating:

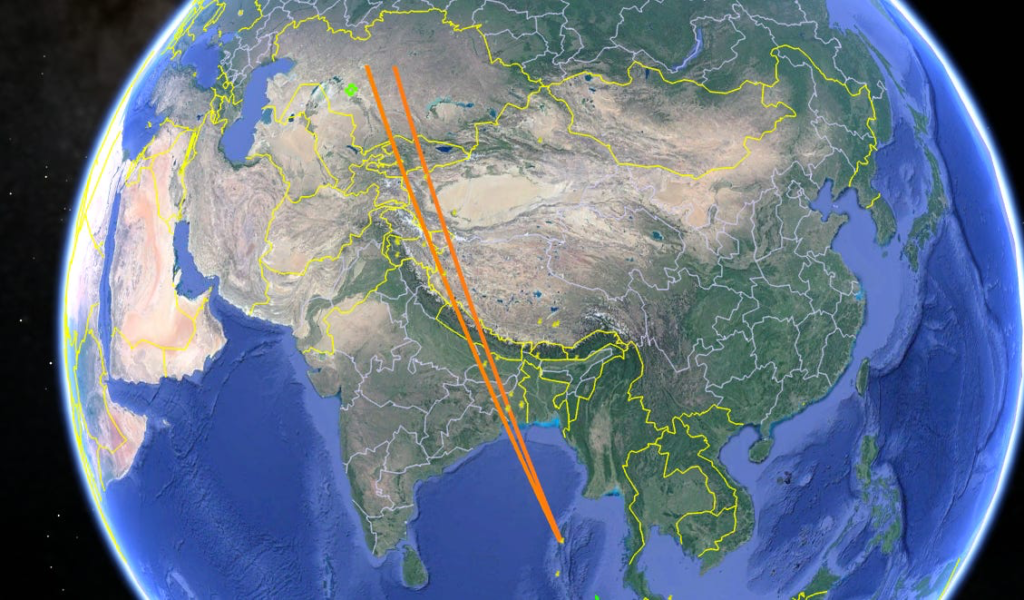

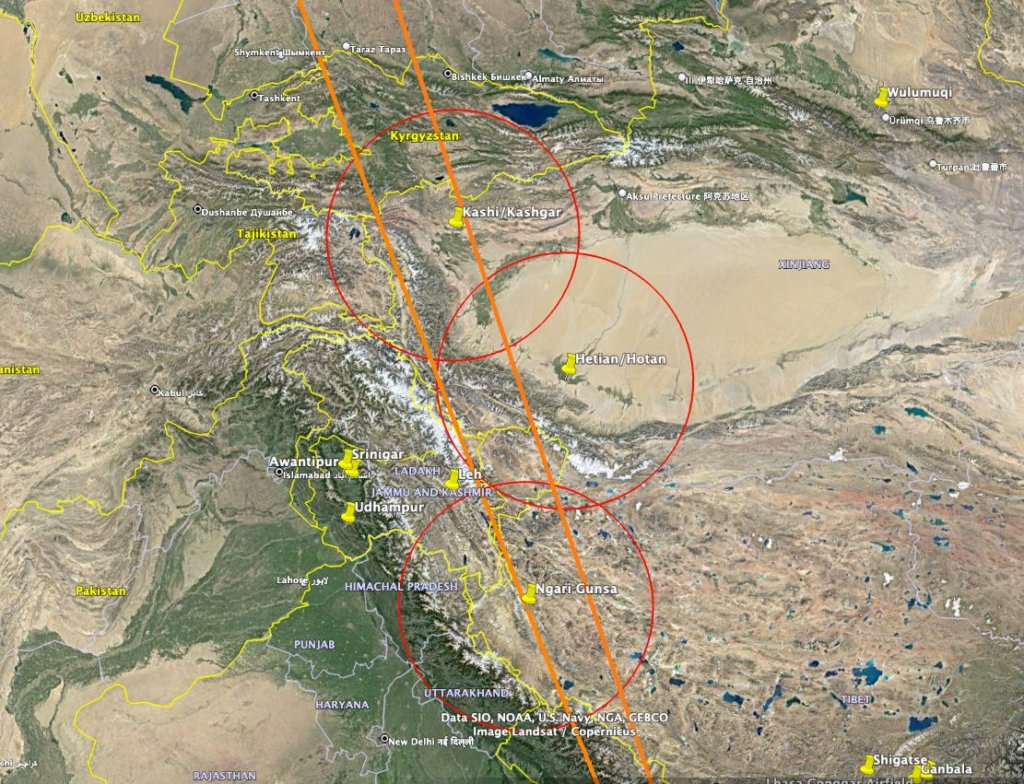

If you plot out the corridor above on Google Earth it looks like this:

As you can see, it’s a pretty tight route, passing over Calcutta and then Tibet before winding up in Kazakhstan.

There has alway been one particularly compelling reason to suspect that the plane had gone south rather than north. If it had gone north, it would have passed through the air-defense radars of multiple countries. Yet no one reported seeing it.

It seems like a common-sense assumption that most countries routinely monitor their whole airspace. That, however, turns out not to be the case. Military radar is expensive to build and requires a lot of electricity and manpower to operate. Unless there is a valuable target to defend, and missiles and planes capable of defending it, running a radar station 24/7 isn’t worth the cost. So in most parts of the world coverage is like Swiss Cheese in reverse: the gaps far outnumber the areas under surveillance.

If MH370 did fly north, what kind of radar environment did it likely pass through?

Let’s start with the beginning of the route. Half an hour after leaving the Malacca Strait, according to the DSTG’s calculations, the plane would have passed over the Andaman Islands. The islands belong to India, which maintains a radar station there. But the radar is only turned on when a crisis is looming, which wasn’t the case on March 8. “We operate on an ‘as required’ basis,” the chief of staff of India’s Andamans and Nicobar Command told Reuters.

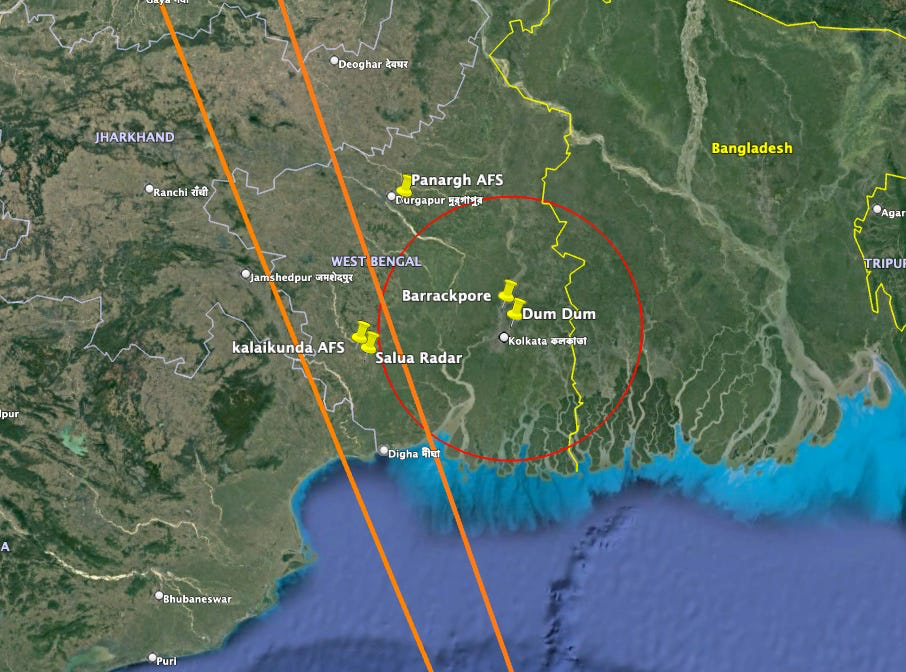

Next, the plane would have crossed the coast of mainland India west of Calcutta and passed almost directly over the Indian Air Force base at Kalaikunda.

The squadron of Russian-built Sukhoi Su-30 fighters based there are guided by the nearby radar installation at Salua. But if the Andaman radar was inactive, Salua likely was as well, since both facilities are geared toward defence of the same area. “Kalaikunda… has been a bridge with the Andamans,” an official told the Times of India in 2011. “The role of the base will grow and aircraft based here will play a vital role in patrolling the skies over the Andamans and the Bay of Bengal.”

It only stands to reason that India would prioritize its radar coverage in more pressing areas, like its border with Pakistan, 1,000 miles to the northwest. Relations between the countries have been tense since they achieved independence from Britain in 1947 with numerous territorial claims unresolved. India frequently intercepts planes that cross into its airspace from Pakistan without adhering to correct air-traffic procedure.

Continuing northward, MH370 would have crossed into Nepalese airspace. Nepal is a small, poor country with no air force or air defense radar.

Passing west of Kathmandu, the plane would have arced over the spine of the Himalayas and entered Chinese airspace. For the next two hours it would have hewn to the westernmost edge of Tibet and Xinjiang, China’s two westernmost provinces.

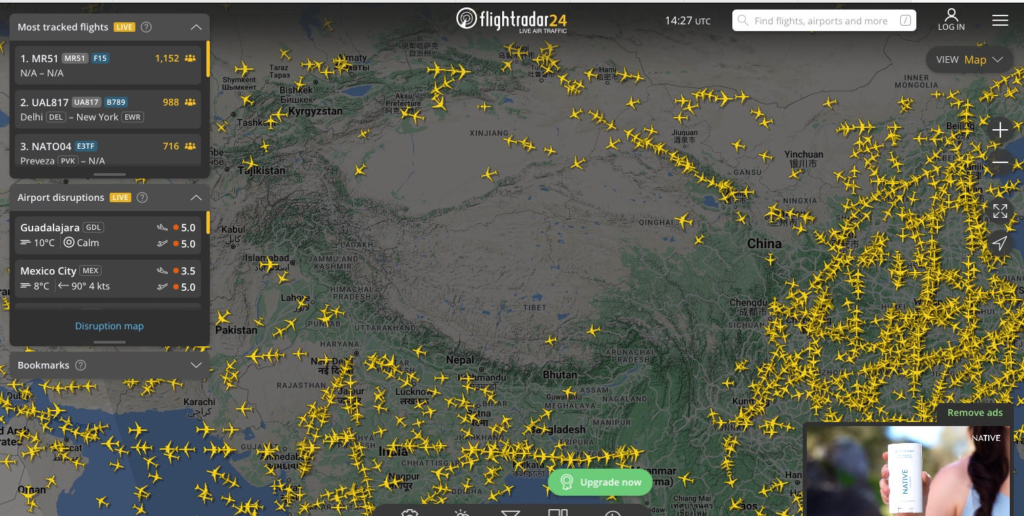

The region is something of an aeronautical desert, as you can see on this real-time flight-tracking web site:

The reason most flights avoid the area is that if a plane should suffer a depressurization emergency and need to descend, it won’t be able to. Even on the ground, the Himalayas and much of the Tibetan plateau are so high that crew members acclimatized to sea level won’t be able to function there. There is one route across far western China that Lufthansa uses to connect Frankfurt and Hong Kong, but it can only be flown by specially trained crews in specially equipped aircraft.

The same conditions that discourage civilian aviation also make the region inhospitable for military aircraft and air defense. Its huge size, remoteness, high altitude, and fierce weather make it difficult to defend; the fact that it is largely empty further means there’s little to attack anyway. The region remains a backwater of Chinese strategic air defence.

“The real threats that China faces are east, along the coast,” says Timothy R. Heath, a senior defense research analyst at the RAND corporation who studies Chinese military aviation. “They have air defenses down south, facing Taiwan and Vietnam, and up near the Korean peninsula, which makes sense because all of those are countries with aircraft and missiles that can harm China. The Indian border is primarily a ground infantry situation, due to the terrain— it’s hard for aircraft to locate and target anything.”

Three Chinese airbases lay on or near MH370’s route.

The first, Ngari Gunsa, is a remote 15,000-foot airstrip laid out along a broad, barren valley in the Gandise range. Its altitude of 14,000 feet makes it the fourth-highest altitude airport in the world. Intended for both military and civilian use, its construction began in 2007 and was completed in 2010. But fighter deployment since then has been infrequent. According to a 2017 article in Indian Defence Review, since 2010 the Chinese air force has been deploying fighter jets only “twice every year for two-week deployment periods.”

About 125 miles after Ngari Gunsa the plane would have crossed from Tibet into Xinjiang. Its path would take it about 100 miles west of Hotan, also known as Hetian, an ancient silk road town on the southwestern edge of the Taklamakan Desert. Hetian appears to have been used as a temporary staging area for fighter planes. There are no military aircraft visible in the Google Earth satellite image of the site take in February, 2013; in September of that year 26 jets and two helicopters can be seen. The following month the ramp is again bare. Then in October, 2014, 16 military jets are visible.

Just before it left Chinese airspace, MH370 would have passed almost directly over the oasis city of Kashgar, also known as Kashi. Google Earth imagery shows that in March of 2014 construction had begun on a new ramp area at the eastern end of the city’s commercial airport. This would ultimately become the home of a fighter squadron. But the first planes wouldn’t arrive for another three years.

Interestingly, in the wake of MH370’s disappearance, China stepped up its overall air defense capabilities in the region, in particular flying “confrontation drills” and “paying much attention to the training of air battle at night,” according to a 2017 story in Delhi Defence Review. In 2015, the Chinese air force deployed its most advanced anti-aircraft missile system, the HQ-9, to Hotan. “It’s kind of odd that they would even have HQ-9s out in Xinjiang,” Heath says. “What’s the threat?”

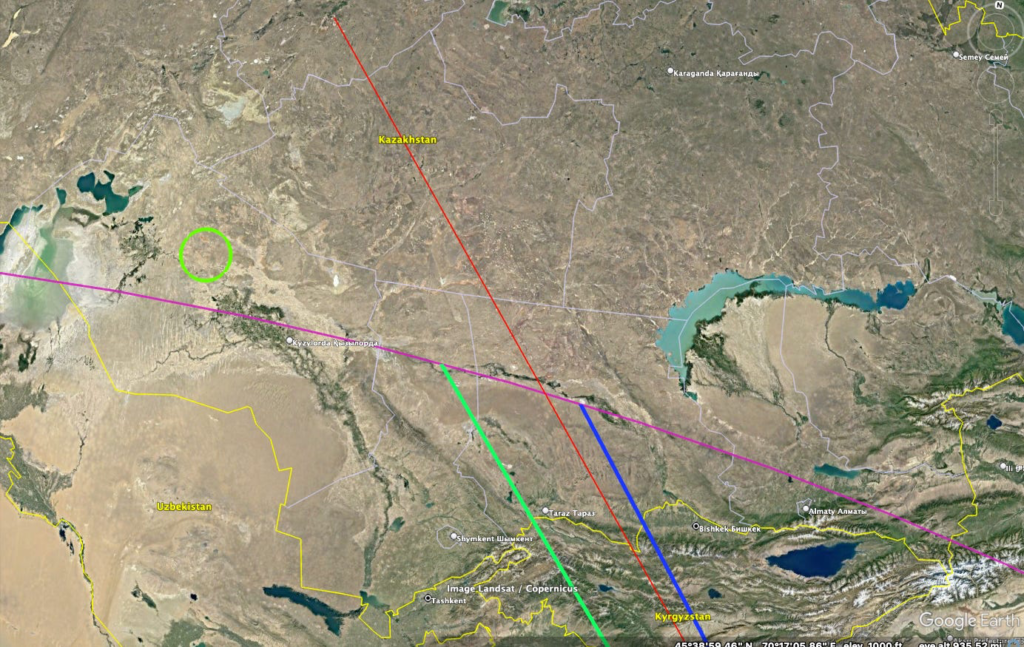

Six hours after diverting from its planned route, MH370 would have been nearing the border of the former Soviet Union. If the hijacking had been commanded by the Kremlin, then the perpetrators would now be home safe. Directly ahead would be the first of the former Soviet states, Kyrgyzstan. Twenty minutes later, the Russian airbase at Kant would lie abeam the starboard wing. Ahead would stretch the expanse of Kazakhstan’s Betpak-Dala desert. And off to the left, about 250 miles away, would lie the Baikonur Cosmodrome. (The green circle on the left, below.)

To watch Deep Dive: MH370 on YouTube, click the image above. To listen to the audio version on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music, click here.