To watch Deep Dive MH370 on YouTube, click the image above. To listen to the audio version on Apple Music, Spotify, or Amazon Music, click here.

For a concise, easy-to-read overview of the material in this podcast I recommend my 2019 book The Taking of MH370, available on Amazon.

Interested in connecting with a growing, passionate audience? Let’s talk. Email andy@onmilwaukee.com.

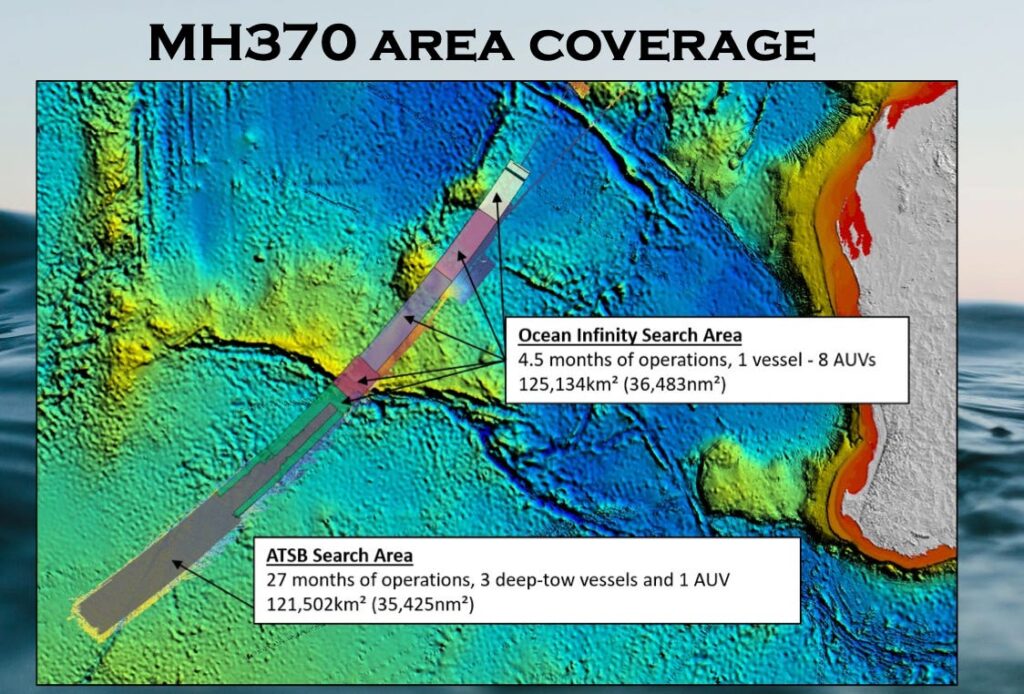

After the Australian government mathematically analyzed the Inmarsat data to figure out where MH370 had run out of fuel in the southern Indian Ocean, they hired a Dutch maritime survey company called Fugro to search a 23,000-square-mile rectangle that encompassed most of the possible endpoints. As we described in Episode 1, the first of three ships assigned to the job began scanning the seabed in October 2014. By the following April, it was clear that the plane was not in fact in the search area, so the Australians doubled its size and asked Fugro to keep going.

But nothing was found.

In November 2016 the ATSB issued a report called “MH370 — First Principles Review” in which they tried to grapple with their failure.

As we’ve talked about before, the Inmarsat data doesn’t work like GPS; it doesn’t give you latitutude and longitude coordinates. Instead, there are a lot of possible routes the plane could have taken that would match the data; the trick to understanding where the plane went is to carry out what’s called a “Monte Carlo simulation” in which you generate a vast number of possible routes and then compare each one to the data to see how well it matches.

Each route has an endpoint; the universe of good-matching routes presents you a universe of endpoints, and these are distributed in a fried-egg pattern that will be familiar to viewers.

A corollary of this dynamic is that for every endpoint in the southern ocean, there is a route that ends there—a story of how fast it flew, how many turns it made, and so forth. What’s important to understand is that in broad terms, it’s physically possible for the plane to fly to any point on the 7th arc by the time of the final ping, but in order to get there in a probabilistially plausible manner you’re left with a much smaller universe of possible enpoints. Other end points are possible but require super unlikely combinations of turns and speed changes. We discussed this in some detail in Episode 11.

So it looks like a fairly straightforward task to search this universe of areas. But by 2016 it was found that the plane wasn’t there. So the obvious question was: why not?

Australian officials decided that the plane must be there, but it must be in a corner that they hadn’t looked in where something implausible but not impossible had happened. As they wrote in their after-action assessment, “There is a high degree of confidence that the previously identified underwater area searched to date does not contain the missing aircraft. Given the elimination of this area, the experts identified an area of approximately 25,000 km² as the area with the highest probability of containing the wreckage of the aircraft. The experts concluded that, if this area were to be searched, prospective areas for locating the aircraft wreckage, based on all the analysis to date, would be exhausted.”

So essentially the Australian position was, it’s there, but we ran out of money to find exactly where, sorry. Let’s pat ourselves on the back and move on.

And then something quite unexpected happened. A private company came forward and offered to re-start the search at its own expense, so long as it would be compensated in the event that it found the plane’s wreckage.

Malaysia announced on January 10, 2018, that it had contracted with Ocean Infinity, a US-registered company, to relaunch the seabed search for MH370. Transport Minister Liow Tiong Lai stated that there was an 85 percent chance that the plane’s wreckage would be found within a 25,000 square kilometer search zone previously demarcated by the Australia National Transport Board.

Australia’s stated position at the time was that if the plane was not found in this area, which stretched from 36 degrees to 32.5 degrees south latitude, it could offer no rationale for looking anywhere else.

Ocean Infinity’s technology was different from Fugro’s, which had mostly pulled along a side-scan sonar behind a ship, and used robot subs for filling in gaps. Ocean Inifinity just used sophisticated AUVs, basically drones. It was more accurate and faster, and they did a bigger area in 1/9 the amount of time. But the result was the same; they didn’t find anything.

They even went way beyond the area that the Australians said was the limit of their analytical justification.

I had long ago hoped that the moment when the seabed search area was exhausted people would start to think that maybe it was time to question the conclusion that the plane must have gone south. But that did not happen.

By the way, when all this was happening, the identity of Ocean Infinity was mysterious. What was this mysterious company that wanted to risk so much money on a long-shot bid? I did some probing around but hit dead ends. Then, last November, Businessweek ran a long piece explaining just who the company was and what they were doing. Turns out, they were high-tech shipwreck hunters backed by some people who were so wealthy they didn’t mind taking an occasional longshot gamble.

From the mainstream perspective, there is still only one scenario that is respectable enough to consider: that the plane went into the southern Indian Ocean. Therefore, the only way to solve the mystery is to keep scanning the seabed, even if you have no analytical reason for doing so.

But even if one were to do this, where would one look?

You can’t just look randomly in the ocean. So you have to ask yourself: of all the unlikely things that might have happened, what is the least unlikely story that would leave the plane outside the area already searched?

One idea is that even though the plane was in a steep dive after running out of fuel (based on BFO data) and small pieces of the interior were found implying that the plane was torn apart in a high-speed crash, that it didn’t maintain a steep dive, but that the captain had a temprorary change of heart and pulled the plane into a shallow gliding descent which allowed him to soar past the limits of the area already searched, before chaning his mind again and putting the plane back into a high-speed dive.

Based on this idea, Victor Iannello and the rest of the independent group are recommending that Ocean Infinity search further awy from the 7th arc — up to 45 nautical miles.

Does this recommendation make sense? Or does it represent the inability to see behond a hypothesis that should already have been rejected?

Further to the barnacles discussion.

Pretty convincing photo for the argument that barnacles don’t grow on surfaces in the air, even when regularly subject to waves and spray.

Side on view of a soccer ball, (which has known dimensions), but you will have to correct for the refractive index of sea water for the barnacles.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2024-03-18/british-wildlife-photography-awards-winning-pictures/103599604?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=twitter&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web

@Ventus45 This is great, thank you!

Love the podcast and continuing analysis. Are you going to spend anytime on discussing possible motives? I’m curious on your thought son this.

Yes! Very soon.