Video shows the spinning rotors separating in midair from the fuselage.

This article originally appeared in New York magazine on April 11, 2025.

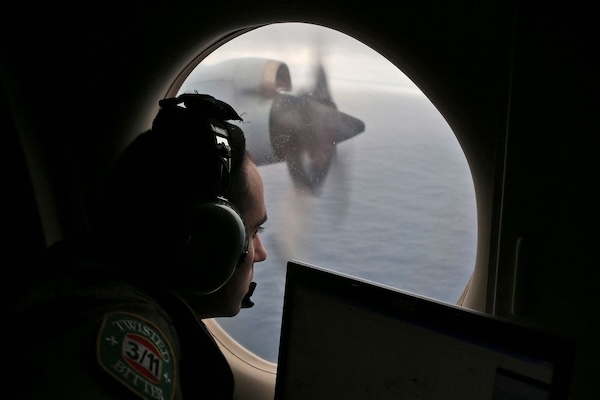

The tourist helicopter that crashed into the Hudson River on Thursday afternoon appears to have fallen victim to a well-known hazard known as “mast bumping,” according to aviation experts. Eyewitness video showed the rotors and the body of the helicopter separating in midair. The phenomenon is unique to helicopters with semi-rigid rotors, like the Bell 206L4 LongRanger that fell out of the sky while flying a family of Spanish tourists. The pilot, two adult passengers and three children were all killed.

The phenomenon of mast bumping arises from the physics of the rotor blades. Each helicopter blade is like a long, thin wing that generates lift as it carves through the air. Spinning at high speed, the blades form a whirring disk. The blades are attached to a hub that in turn is connected to a mast that projects vertically upward from the transmission. To visualize the relationship of the mast and the rotor hub, says Robert Joslin, a professor at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University, in Daytona, Florida, “Think of a drinking cup upside down on the top of a broom handle. If you just move it back and forth a little bit, it won’t touch. But if you go real hard, the rim will hit the handle.” In the case of the helicopter, the hub is a fast-spinning hunk of metal that could bend the mast or break it altogether, severing the rotor and sending it flying.

Continue reading Why a Helicopter Broke Apart Over the Hudson River